The English version of “Một Giờ Với Bà Jackie Bong-Wright” (translated by Jackie Bong-Wright)

Eighty years old, but totally alert. Ms. Bong-Wright can describe the details of the past as if time cannot destroy her memory — from the story of her late husband, Professor Nguyen Van Bong, Rector of the National Institute of Administration, Republic of Vietnam, assassinated in Saigon 50 years ago (November 1971) to the social and cultural activities she organized after migrating to the U.S. Her name is Jackie Bong-Wright – a witness to the Vietnam War – which not only she, but also her whole family, played a part in. Talking to her on the eve of the Tet Lunar New Year of the Buffalo 2021, brings to mind the images and memories of history, and also envision the incredible energy of a unique role model: “western” in her thoughts, but very “eastern” in her traditions and the Asian philosophy of life.

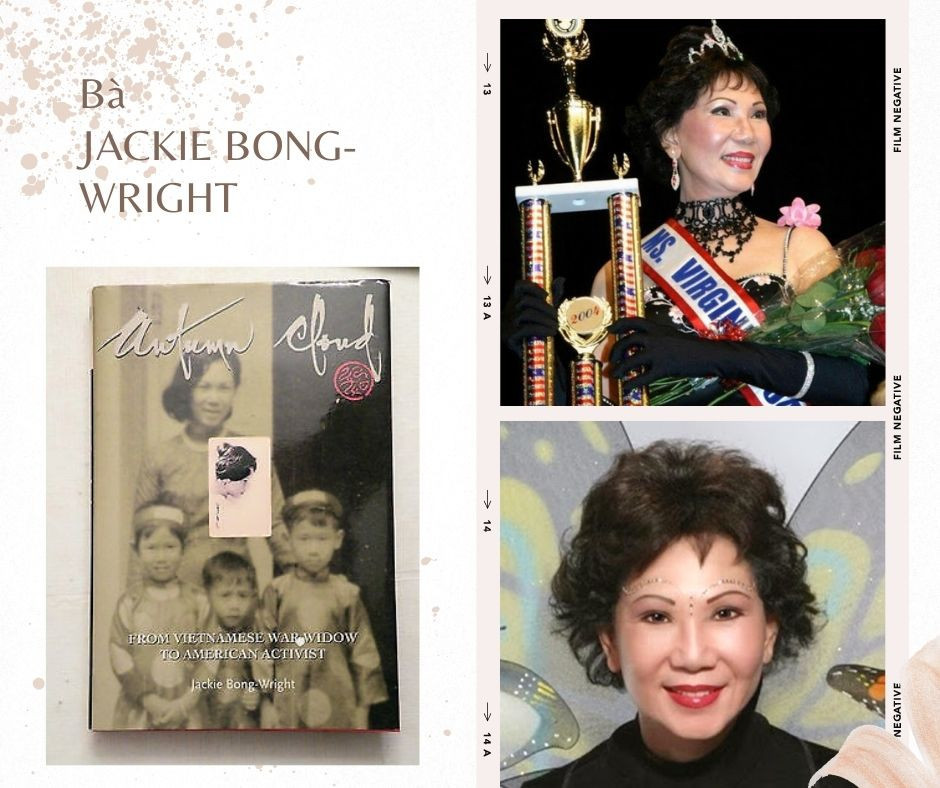

Her Vietnamese name is Le Thi Thu Van. She likes to describe herself as a multi-colored butterfly, roaming around the globe, sampling cultures and bringing harmony wherever she lands. It’s impossible to desribe all the contributions she has made to the Vietnamese community over the past four decades since landing in America. It’s also hard to imagine a petite lady – similar to First Lady Nancy Reagan, who invited her to the White House – with so much passion inside her. Her way of life depends on a strong faith. Faith has helped her overcome the many challenges she has had to overcome, and faith has also helped her endure the retributions that come with activism. She likes to say, “Success is not how high and fast you reach the top, but how high and fast you bounce back when you hit the bottom.” What were the events that brought you to your lowest point, I asked.

“First was the assassination of my late husband, Nguyen Van Bong, after we’d been married only six years. We had three young children. I was 30. His death left me in ruins. I could not move for many days. I cried so much that I could not even read. I didn’t know whom to blame. One of my sisters had converted to Communism and gone up north, while two brothers fought in the army of the Republic in the South. My husband had been the leader of the Opposition Party to President Nguyen Van Thieu.

I could not eat or sleep. Family members took me to the Chinese part of Saigon to get herbal treatments from a Chinese herbalist. I started to recover. What was most important, I thought, were my children. What would happen to them if I was not there for them? They were my reason for bouncing back. Remembering my husband, with the strength of will to overcome poverty and study hard enough to become an outstanding professor, filled me with the motivation to become strong and stand up like him. So, two months later, I stopped teaching French at the Allaince Frencaise and went to work as the Director of Cultural Activities at the Vietnamese American Association, a non-profit organization sponsored by the U.S. Information Service.”

Ms Bong-Wright organized lectures, conferences, concerts, cultural events, exhibitions, vocational training classes. She was also involved in women’s rights. She actually carried out a “revolution” of a kind that had never been seen in the South. She lobbied the Vietnamese Parliament to pass a family planning law, despite severe criticism that she was advocating abortion and killing babies. In fact, she was only educating women to space their deliveries and have fewer children. She became one of the most brilliant women in the social and political arenas at that period in the Republic of Vietnam, although she was not a politician nor did she have any political ambitions. She bounced back so strongly that the American media quite often characterized her as a prominent community activist. In 1972, Ambassador to Vietnam Ellsworth Bunker invited her to a lunch in Saigon for Nancy Reagan, wife of the Governor of California, who later became First Lady. In 1973, the New York Times interviewed her, and she was invited later by the United Nations to represent South Vietnam at an international Conference on the Status of Women.

The young widow bounced back a second time after arriving in America in 1975. If she had lost a husband in 1971, she lost averything in 1975. She had to figure out how to restart her life from scratch, with only her two bare hands. She could not find work anywhere. Born into a priviledged family, she had lived in abundance, studied at a French school in Dalat, attended college in France and England and, later, in the U.S. But although she held a BA from France, she had no diploma in typing – the skill she needed to find a job in that moment. Instead, her only abilities were in languages and diplomacy. She felt unfit, and grieved for her lack of talents. But once more, she thought of her children and bounced back.

With the sponsorship of Ambassador Bunker, she adapted herself to a new way of life. She went to work at the Lacaze Gardner school in Washington, at a time when arrivals of Vietnamese refugees were increasing. She focused on assisting them. She became a member of the Asian Pacific American Women and lobbied the U.S. Congress to help with resettlement. She established the Indochinese Refugees Social Services, opened a shelter, and organized vocational training for the new arrivals. After seeing that her work had somehow borne fruit, she registered at Georgetown University and studied with Dr. Madeleine Albright, who later became Secretary of State under President Bill Clinton. Two years later, in 1984, she graduated with a Masters degree in Foreign Relations.

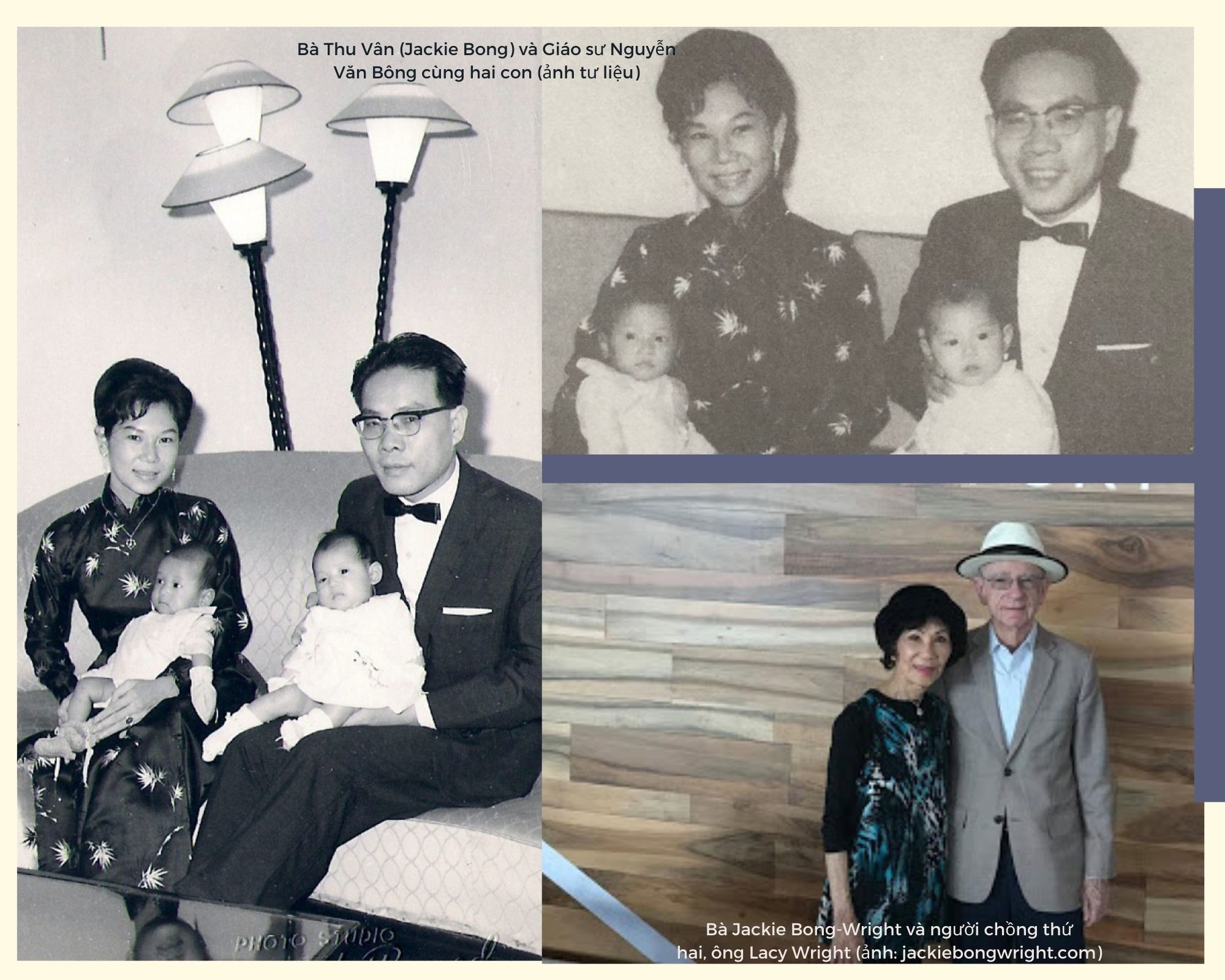

The third time Jackie bounced back, or, more accurately, regained more of her fire and faith, was her love for Lacy Wright, a foreign service officer with the Department of State. “He gave me my hope back. He brought me out of my depression. He loved me and gave me tenderness and care. He also loved my children, and played with them, put them on his shoulders, and cared for them as his own. He gave me not only happiness but also faith in myself. I bounced back with his love,” she recounted.

Mrs. Jackie Bong-Wright (at her home, February 2021 – photo by MK)

Mrs. Jackie Bong-Wright (at her home, February 2021 – photo by MK)

Mrs. Jackie Bong-Wright and her husband, Mr. Lacy Wright (at her home, February 2021 – photo by MK)

Mrs. Jackie Bong-Wright and her husband, Mr. Lacy Wright (at her home, February 2021 – photo by MK)

Although she did not say it, each time she bounced back, she rose even higher. In 1999, she founded and became President and CEO of the Vietnamese American Voters Association, registering Vietnamese Americans to vote. She organized events for the Vietnamese community. In 2003, Washingtonian Magazine named her a “Washingtonian of the Year” for her 27 years of service to the community in the Washington area. Two years before, in 2001, she published her autobiography, Autum Cloud: From Vietnam War Widow to American Activist.

There is more. She became a writer for Asian Fortune News, and a producer for two Vietnamese radio and TV entities. Having learned of a Pageant for Seniors in Virginia for women of 60-plus, she was encouraged to apply and did so at the last minute, the only Asian contestant and the only one with a Masters in International Relations. She was unique, too, in being the sole community organizer, having organized numerous social activities and multi-cultural programs. And she was the only “butterfly,” having flown all around the world and having lived everywhere from Vietnam to Cambodia, Laos to France and Italy and South America and the Caribbean, sampling local cultures everywhere.

Ms. Bong-Wright was also the personifier of that period’s unique Vietnamese woman, a witness to American society that women from Vietnam were not just people on public welfare, not just housewives, and not just employed in simple jobs, but also people able to “bounce back” and make valuable contributions to society. The result: Jackie Bong Wright was crowned Ms. Senior Virginia. That victory showed what it meant to triumph, to bounce back, and to be a role model for others. To break into the mainstream, you have to know what to do and how to do it – not just shout and wave flags.